The city is a semiotic landscape [1], consisting of constellations of various community groups, interests, and power relations. It is now expected that the urban environment will become an arena for class and group battles — such as which group can dominate other groups and which gang can be ‘cooler’ than other gangs. These discourse ‘battles’ are present in the symbolic realm, one of which is the creation and distribution of artifacts [2] in the form of stickers.

Who doesn’t know about stickers? Stickers are omnipresent for urban dwellers and have taken various forms throughout the world’s civilization.

At the dawn of time, stickers were substantially associated with a term no less popular: graffiti, a word derived from ‘graffito’ in Italian, which refers to any scribble drawn on public surfaces. During the Roman Empire, poetry, obscene expressions, slogans, and even philosophical thoughts were commonly found in the catacombs. The earliest known example is the Alexamenos graffito, allegedly the first pictorial depiction of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ [3].

Regarding its practicality, many historians believe the first stickers may date back to ancient Egypt. Archaeologists have found remains of papers plastered on the walls of old markets to display the prices of goods. Perhaps they used the same adhesive that was used to wrap their mummies?

Alexamenos graffito, one of the graffiti found during the Roman empire, circa 200. This graffiti is allegedly the first pictorial depiction of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Along with the progression of time and the onset of industrialisation, it is no longer necessary to painstakingly inscribe thoughts or heartfelt expressions by hand, as these can now be represented through written and visual works crafted by graphic artists or organisations, produced on paper or plastic that can be affixed to any surface.

In 1935, the American inventor R. Stanton Avery, also known as the father of modern stickers, developed a pressure-sensitive machine capable of producing self-adhesive labels with peel-off backings that could be die-cut into any size or shape. This marked the birth of the sticker as we know it today.

The first advertisement for modern sticker produced by Avery Labels. Circa 1935 (Source: averydennison.com)

Avery Labels, the first modern sticker circa 1935. (Source: averydennison.com)

No one can pinpoint the exact year when stickers began to be produced in Indonesia, but it is argued that stickers first appeared in the country as early as the 1970s. Since then, urban stickers have become abundant in various Indonesian cities, omnipresent in public vehicles, notably angkot (city transports), doors, storefronts, and numerous other locations.

In ‘Stiker Kota,’ published by Ruang Rupa, Ardi Yunanto classifies two categories of sticker consumers, derived from a famous Indonesian slogan, ‘bebas tapi sopan’ (free but polite): The civil and gracious individuals, who utilize stickers for wise words and religious texts, perhaps seeking to ‘illuminate’ their viewers, and the liberals, who aim to express themselves through commonly erotic or occasionally offensive language [4].

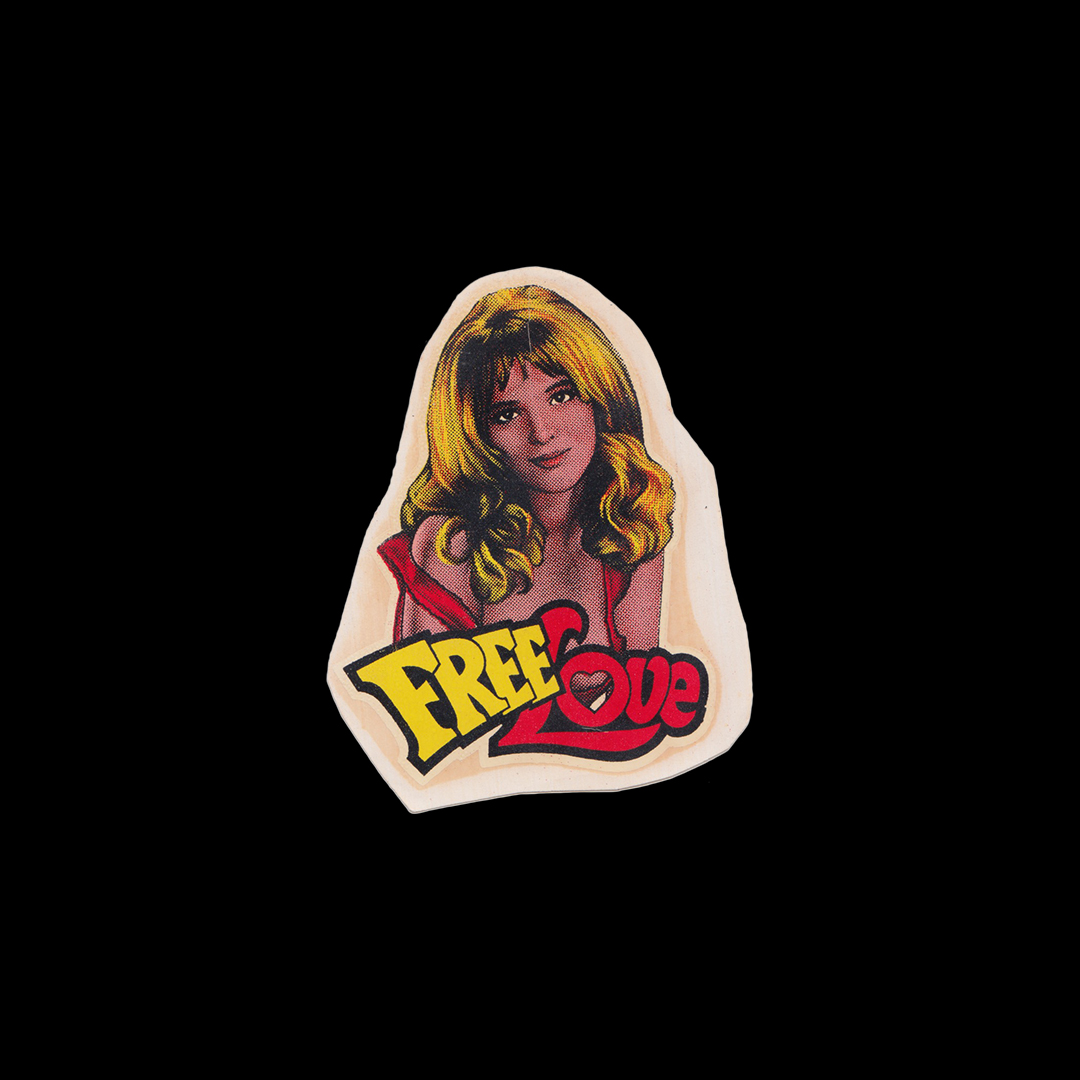

Our Grafis Nusantara’s sticker collection portrays an array of Indonesian urban stickers from the 1970s to the 1990s featuring these two categories – ranging from the wise words of Jesus Christ to erotic stickers.

A religious sticker. (Source: Rakhmat Jaka, Grafis Nusantara)

An erotic sticker. (Source: Rakhmat Jaka, Grafis Nusantara)

Today, these stickers exist not only in physical form. On social media, we encounter various types of stickers that are traded and sent via messages. What’s even more interesting is that these online stickers are no longer exclusively produced by specific creators, as anyone can now create their own.

![[D/R]ekonstruksi](https://grafisnusantara.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/DSC29481-OK-3-1-scaled.jpg)